Where did Giving Tuesday come from, and why should you and your organization care about it? While a new social movement to encourage generous donations during the holiday season, Giving Tuesday also calls us to act on giving effectively. In this article, we’ll cover the basics of Giving Tuesday and how you can be a life-long participant.

Giving Tuesday was created in 2012 and is celebrated on the Tuesday after US Thanksgiving. An answer to the myriad holiday-discount-retail days (i.e., Black Friday, Cyber Monday), it encourages individual and collective generosity through its own “distributed network of leaders.”

From GivingTuesday.org:

The movement continues to grow in year-over-year donation volume, reach and impact—driving increased donations and behavior change. In 2021, an estimated $2.7 billion were donated in twenty-four hours in the U.S. alone, a 9% increase over the prior year and a 37% increase from pre-pandemic levels. On November 30, 2021, 35 million adults [participated] by offering gifts of time, voice, skills, goods, and money, as well as countless acts of kindness inspired by the movement.

Fast Facts about Giving Tuesday

More than just a day of the year, Giving Tuesday has a team of nonprofit professionals working to spread initiatives that encourage generosity at all levels.

- The Giving Tuesday team has the Data Commons, which uses data sharing and analysis to identify “innovative practices that can help grow generosity” with the support of 50 global data labs.

- As an emergency response to the spread of COVID-19, on May 5, 2020, #GivingTuesdayNow trended on social media on a day when online donations in the United States amounted to about $503 million.

- There is no specific political or advocacy cause that drives Giving Tuesday, but it was founded by the 92Y’s Center for Innovation and Social Impact and is supported by organizations like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, PayPal, Ford, and more.

- It is currently not known exactly how much money raised is directly attributable to campaigns like Giving Tuesday, but Giving Tuesday’s team estimates that donors gave $808 million online and $2.47 billion overall.

- Organizations can easily spread the word about Giving Tuesday and participate through publicly available logos, sample press releases, and social media toolkits and templates.

While there may be no perfect answer to the attention economy that nonprofits have to compete in, it’s often the case that engendering general audiences online with messages of generosity and awareness of social causes can affect their giving habits. For example, one report from 2017 found that social media “play[ed] a role” in 35 percent of all donations to surveyed organizations.

That’s not nothing.

How to Give Effectively

In social services, we’re no strangers to the never-ending problem of fundraising, so when asked to give to other causes, how do we personally choose how to spend what little extra time, effort, and money we have? After all, some charities are more effective than others.

Peter Singer, a professor of bioethics at Princeton University, has studied this issue deeply. In his now-famous TED talk, Singer supports the claim that our charitable impulses are sometimes irrational in the sense they often don’t align with the most urgent social ills. For example, you’d probably feel the understandable impulse to help a distressed child in your own neighborhood (a very empathetic response) more strongly than to donate to a far-worse-off child in a developing country.

Helping the neighbor child will give you immediate, positive feelings, but does that mean you’ve done your “good deed for the day”? By no means should we stop at helping our neighbors, argues Singer, also a thought leader in the Effective Altruism (EA) movement:

[Effective Altruism is] important because it combines both the heart and the head. . . Reason helps us to understand that other people, wherever they are, are like us, that they can suffer like we can, . . and that just as our lives and well-being matter to us, [they] matter just as much to all of these people.

In other words, our emotional or physical proximity to the people-centered causes we give to shouldn’t matter as much as the lives we save. “But,” you might say, “I’m no billionaire like Bill Gates and can’t give much money. How much impact can I really have?”

Singer responds to this objection with the story of a man who worked in academia, not exactly the most lucrative of career choices:

[Toby Ord] became an effective altruist when he calculated that, with the money he was likely to earn throughout his academic career, he could give enough to cure 80,000 people of blindness in developing countries, and still have enough left to have a perfectly adequate standard of living.

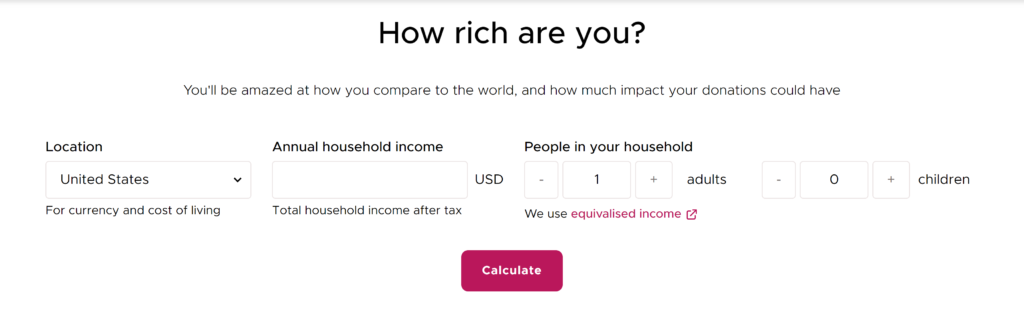

From that calculation came GivingWhatWeCan.org, which is affiliated with EA and contains a calculator that determines a suggested automated donation amount based on your household income.

The Most Effective Charities

Effective Altruists refer to this page as a guideline for choosing charities, with these steps:

- Choose a cause to support that is generally

- large in scale, which impacts many lives;

- neglected, which means they need outsized support; and,

- tractable, which means there are obvious, measurable ways to make progress.

- Choose a fund or charity that is generally

- evidence based, which means they rely on unbiased, peer-reviewed research;

- cost effective, which means their overhead costs are streamlined;

- transparent, which means they report on their outcomes consistently and fairly;

- scalable, which means they have room for more funding immediately; and

- known to report positive outcomes.

- Automate your donations if possible. Doing so makes giving a habit you don’t have to set reminders for.

One example of an extremely effective charity is the Against Malaria Foundation, which is top rated by GivingWhatWeCan and GiveWell. This organization has saved more lives than most charities at an incredibly effective impact of 400,540,275 people protected from malaria.

All of this isn’t to say that it’s a bad idea helping your elderly neighbor carry her groceries, or housing a refugee family, or volunteering at a local food provider. Giving personal effort can have a positive community-building aspect that’s difficult to replicate with funding alone.

But as you know, data is the lifeblood for evaluating social determinants of health (SDoH) outcomes, and those are the most urgent outcomes we should strive to improve in our giving. On this Giving Tuesday and beyond, let us find global causes that impact lives in immeasurable—and measurable—ways.